Explaining inclusive classrooms concept: an overview

Research article  Open access |

Available online on: 04 May, 2023 |

Last update: 04 May, 2023

Open access |

Available online on: 04 May, 2023 |

Last update: 04 May, 2023

Abstract

Ensuring children with disabilities attend school alongside their classmates and neighbors while simultaneously receiving the extra education and assistance they require to excel as students and meet high standards is known as inclusive education. According to the inclusive education ideology and practice, all students should be considered part of the general education community, regardless of their labels. This ideology promotes the fusion of the special education and public education systems into a single system that is responsive to the requirements s of all learners rather than the continued existence of two separate systems. Hence in inclusive classrooms, by adopting an inclusive pedagogy approach and use of education-assistive technology, every student gains. Inclusive classrooms improve the capacity of all children to cooperate, comprehend and appreciate various points of view, think critically, and be effective learners.

Keywords- Inclusive education, accessibility, inclusive classrooms, students with disabilities.

Introduction

The number of disabled children globally is projected to be 240 million. Children with impairments have aspirations and plans for the future, just like any child. To develop their abilities and reach their full potential, like all children, they require access to high-quality education (UNICEF, 2022). All students, particularly those with differing talents, needs, and impairments, have the right to equitable learning experiences. According to the comprehensive definition provided by UNESCO (2009), inclusive education comprises improving the educational system’s ability to reach all learners in a way that promotes fairness for all learners, particularly those with disabilities (Khribi, 2021).

The education of learners with disabilities in inclusive classrooms becomes more of a shared responsibility between the various stakeholders when all learners’ capabilities or “differential abilities” are acknowledged (Ahmad, 2015a; Praisner, 2003). This requires a change in attitude; the classrooms infrastructure, pedagogy, need-based approaches, and materials for delivering education, assessing students’ progress, and evaluating teachers are all readily available and accessible, as well as the much more apparent issue of acceptance (Ahmad, 2014; 2015b; Stainback & Stainback, 1984). A general education classroom that welcomes students with and without learning difficulties or disabilities is called an inclusive classroom. Inclusive classrooms are friendly and meet all children’s academic, social, emotional, and communication requirements. Therefore inclusion must be practiced successfully at all levels of education, including in the community, the school, the classroom, and the lesson (Eredics, 2022).

Teachers in inclusive classrooms support students’ access to and understanding course material by implementing inclusive instructional practices, including Universal Design for Learning (UDL), lesson adjustments, and even curriculum adaptations. Students who are different in various ways and those with impairments face this difficulty regarding inclusion. Education professionals must accommodate students with varied learning styles, languages, homes, family situations, and hobbies.

Benefits of Inclusive Classroom

Both people with impairments and those without gain more knowledge. Over the past three decades, several studies have revealed that inclusive education benefits students with disabilities and their classmates without difficulties, with students with disabilities achieving higher accomplishments and developing better skills (Alquraini & Gut, 2012). This includes academic progress in literacy, (i.e., reading and writing, arithmetic, and social studies, both in class and on standardized exams, as well as enhanced communication, social skills, and friendships). Fewer absences and referrals for disruptive conduct are also linked to more time for students with disabilities in the regular classroom. Generally, students have a greater self-concept, like schools and their instructors, and are more driven to study and learn. These discoveries concerning attitude may have something to do with this.

Moreover, finding new instructional approaches is another aspect of the benefit of inclusion that enables classrooms to incorporate all students actively. It also entails figuring out how to foster connections, friendships, and respect for one another among all students and between students and instructors in the classroom. Also, inclusive classes offer better learning chances when students with disabilities learn in classrooms alongside other children; children of all levels are frequently more motivated to learn. Finally, inclusive classrooms can promote parental engagement in their children’s education and the goings-on at their neighborhood schools.

Inclusive Classrooms Strategies

The key to successful inclusive education in classrooms has been recognizing and comprehending student diversity, including cognitive, academic, social, and emotional traits (Rosmiati et al., 2019). Below we are going to explore some of the strategies that are adopted around the world for creating inclusive classrooms:

- Least restrictive environment: The assumption underlying how the school and classroom function is that kids with disabilities are equally capable to students without impairments. Because of this, every student may actively participate in their classes and the wider school community. The legislation and strategies in many countries, including Qatar, requiring that people get their education in the least restrictive environment is a significant component of the movement (LRE). This indicates they are as integrated as possible with their typically developing classmates, with general education being the setting of choice for all people (Alquraini & Gut, 2012). However, this is not to argue that students never need to take time away from their usual studies; they occasionally do for specific reasons, such as speech or occupational therapy. The objective is for this to be the exception, however.

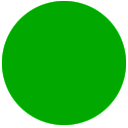

- Pedagogical and teaching strategies: to create inclusive classrooms, pedagogical training methods investigate learning obstacles such as unconscious bias, microaggressions, stereotype threat, and fixed mindsets, as well as the social identities of students and instructors. Therefore, we need competent and trained teachers who are knowledgeable and confident about educating students with disabilities and are familiar with inclusive classrooms’ pedagogy, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Inclusive Pedagogical Process (Inclusive Pedagogy 2022)

Figure 1: Inclusive Pedagogical Process (Inclusive Pedagogy 2022)

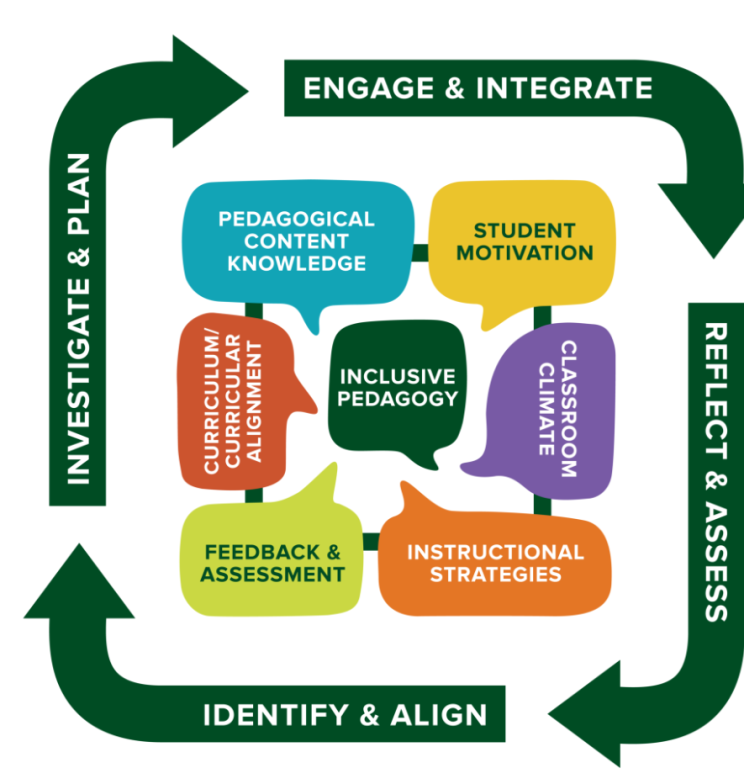

- Use A Variety of Instructional Formats: Transition from whole-group teaching to flexible groupings, such as small groups, stations or centers, and partnered learning, starting with whole-group instruction. Using technology, such as interactive whiteboards, is associated with high student involvement across the board. Flexible groups can be student-led with teacher oversight for older students but are frequently teacher-led for younger children. Peer tutoring, cooperative learning groups, pair work, and student-led presentations are all examples of peer-supported learning that may be highly successful and interesting. Diversity in the teaching methods and accessible resources is seen in Figure 2.

- Accessible Academic Curriculum: All students must be allowed to engage in learning activities with the same learning objectives. Although this will need considering the specific assistance that each student with a disability requires, general tactics include ensuring that all students hear instructions, that they really begin tasks, that they take part in large-group education, and that they exit the classroom simultaneously. Regarding the latter, it would keep people on duty with the teachings and prevent their non-disabled peers from observing them leaving or arriving during class, which can significantly highlight their differences.

Figure 2: Learning Pyramid National Training Laboratories

Figure 2: Learning Pyramid National Training Laboratories

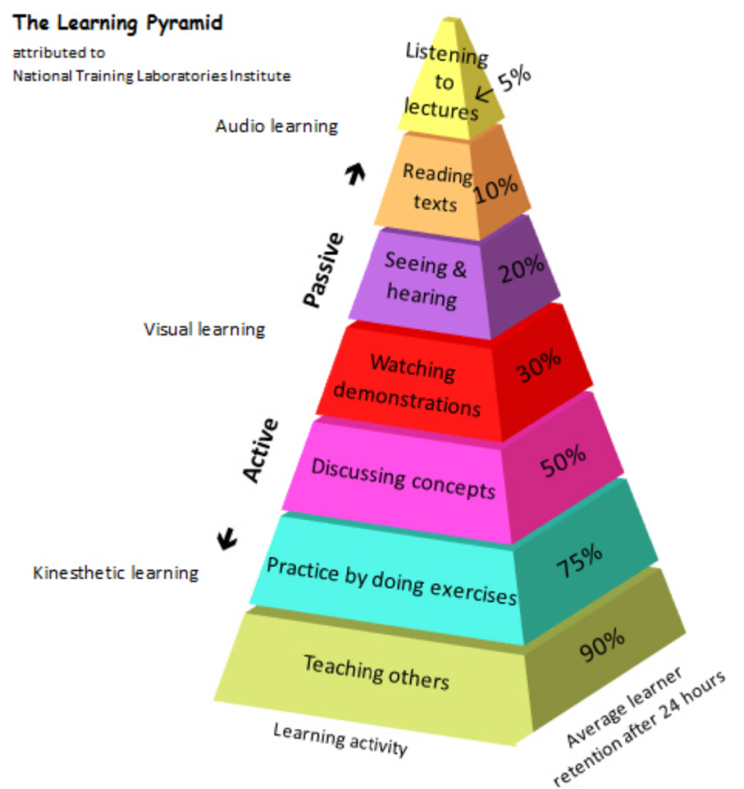

- Use of Universal Design: These techniques are diverse and meet the demands of several learners. They contain a variety of mediums, such as models, pictures, objectives and manipulatives, visual organizers, oral and written replies, and technology, for both providing knowledge to students and enabling students to present learning back (Figure 3). These can also be modified to accommodate students with disabilities who use giant print and headphones, can have a peer transcribe their dictation, draw a picture in place of writing, use calculators, or have more time. Consider the effectiveness of project-based and inquiry-based learning, in which students research an experience independently or in groups.

Figure 3: Inclusive Classrooms Quality Approaches

Figure 3: Inclusive Classrooms Quality Approaches

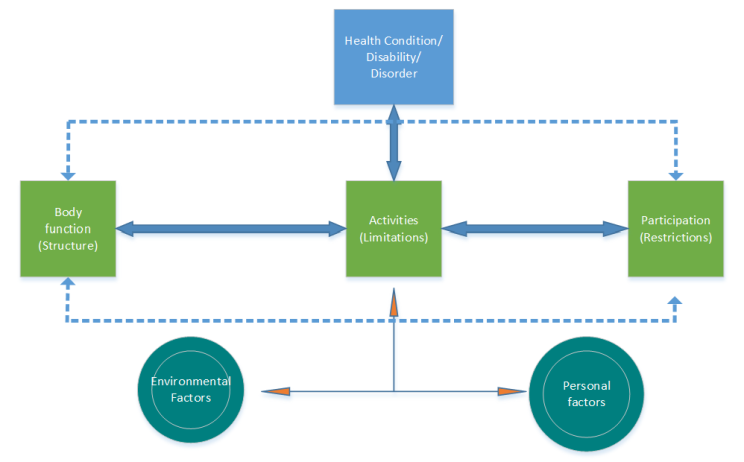

Assistive Technology & Disability

The World Health Organization (WHO) developed the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), which recognizes the numerous obstacles faced by children with disabilities in their educational experience and uses the term “participation” rather than “inclusion” (ICF, 2001; Simeonsson et al., 2003). It turns the conversation away from typically being very child-focused and toward environmental elements that impact and may even help children participate more fully in their daily lives (ICF, 2001; Simeonsson et al., 2003; Gal et al., 2010). Therefore, “functioning” and “disability” are understood as “multi-dimensional” terms linked to people’s bodily structures and functions, their activities and regions of participation in life, and the environmental circumstances that influence these experiences, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4: ICF Model of Disabilities (ICF, 2001)

Figure 4: ICF Model of Disabilities (ICF, 2001)

Assistive technology can certainly help close the gap between non-disabled and students with disabilities by “assisting” in the practice of teaching students with physical, mental, and developmental disabilities in the same classroom (Smith et al., 2005); by removing obstacles that had been preventing them from learning on the same level as their peers, they are better able to understand the material. Assistive technology can be described as any piece of equipment or device in the market or modified that improves the lives of persons with special needs, disabilities, or impairments is considered assistive technology (AT). While assistive technology might be low-tech or completely non-tech, integrating assistive technology can make classrooms more accessible. ”The real miracle of technology may be the capacity it has to remove previously insurmountable barriers faced by persons with disabilities” (Simon, 1991). Since many of these technologies serve as supplements for students with particular requirements, using educational assistive technology can make accommodating and involving learners more straightforward. For instance, text-to-speech for deaf and hard-of-hearing people is a simple approach to involve those learners in general education classes.

Conclusion

Numerous factors make inclusive classrooms necessary. However, they are also a part of a broad range of methods that instructors may employ to improve not just the education of all students but also the opportunity for each student to use technology (ViewSonic, 2022). Inclusive classrooms are incredibly beneficial for students who receive special education. A large number of students with special needs, disabilities, or impairments are capable of participating in regular classrooms.

While some studies demonstrate the advantages of inclusive classrooms, detractors claim that this methodology is flawed because the students who spend more time in inclusive classrooms tend to be better suited to those environments and perform better than their less-suited ones peers outside of these classrooms.

The argument made by those opposed to inclusive education is that while inclusion for all students is prioritized, people with disabilities are not recognized as unique individuals with complex needs that might not be satisfied in a big classroom. Additionally, detractors cite data that shows that peers of kids with disabilities in inclusive classes frequently suffer disadvantages (Bruno, J. R, 2019).

References

Ahmad, F. K. (2014). Assistive provisions for the education of students with learning disabilities in Delhi schools. International Journal of Fundamental and Applied Research, 2(9), 9–16.

Aldabas, R. A. (2015). Special education in Saudi Arabia: History and areas for reform. Creative Education, 6(11), 1158.

Bruno, J. R. (2019). Teachers’ Attitudes and Perceptions of Students with Disabilities (Doctoral dissertation, Northeastern University).

Eredics, N. (2022). Inclusive Classrooms: Getting Started. Reading Rockets. https://www.readingrockets.org/article/inclusive-classrooms-getting-started

Gal, Eynat., Schreur, Naomi. and Engel-Yeger, Batya. (2010): Inclusion of Children with Disabilities: Teachers’ Attitudes and Requirements for Environmental Accommodations. International Journal of Special Education vol. 25 no 2.

Khribi, M. K. (2021). Inclusive icts in Education. Nafath, 6(17). https://doi.org/10.54455/mc.nafath17.03

ICF (2001): “International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.” World Health Organization, ISBN-13: 9789241545440, 228 pp.

Inclusive education. UNICEF. (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2022, from https://www.unicef.org/education/inclusive-education

Inclusive Pedagogy. Colorado State University. (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2022, from https://tilt.colostate.edu/prodev/teaching-effectiveness/tef/inclusive-pedagogy/ip-pedagogical-practices/

Praisner, C.L. (2003): “Attitudes of elementary school principals toward the inclusion of students with disabilities.” Exceptional Children vol.69, no.2, 135–146.

Pyramid, L. National Training Laboratories. NTL Institute for Applied Behavior Science, 300.

Rosmiati, R., Ghafar, A., Tabroni, T., & Rahman, A. (2019). The Inclusive Education Program in Jambi: Voices from Insiders. Indonesian Research Journal in Education| IRJE|, 199-208.

Simeonsson, R.J., Leonard, M., Dollar, D., Bjorck-Akesson, E., Hollenweger, J., and Martinuzzi, A. (2003). “Applying the international classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF) to measure childhood disability. Disability and Rehabilitation vol.25 (11-12), 11-17.

Smith, R.W., Austin, D.R., Kennedy, D.W., Lee, Y., & Hutchinson, P. (2005). Inclusive and special recreation: Opportunities for persons with disabilities (5th Ed.). Boston: McGraw Hill.

What is an Inclusive Classroom? And Why is it Important? ViewSonic. (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2022, from https://www.viewsonic.com/library/education/what-is-an-inclusive-classroom-and-why-is-it-important/