Bridging the Gap Between Autism Research and Community Needs: A Participatory Framework for Culturally Responsive Research

Research article  Open access |

Available online on: 27 January, 2026 |

Last update: 27 January, 2026

Open access |

Available online on: 27 January, 2026 |

Last update: 27 January, 2026

Abstract-

At the heart of AutismTech 2025 in Doha, two expert-led panel discussions brought to light the ongoing disconnect between autism research and the everyday realities of autistic individuals, especially within Arabic-speaking communities where cultural and linguistic nuances are often overlooked. Although scientific understanding of autism has advanced globally, much of this progress has yet to translate into meaningful change for families and individuals in the Arab region. The sessions gathered a diverse group of voices—self-advocates, caregivers, clinicians, researchers, and policy leaders—who shared a common concern: research priorities often fail to reflect the lived experiences and needs of the communities they aim to serve. Through a detailed thematic analysis of the discussions, four recurring challenges became evident: a misalignment between research agendas and real-life needs, the absence of culturally adapted tools and communication methods, limited community involvement in the research process, and inadequate channels for sharing findings in accessible ways. In response to these challenges, participants collaboratively shaped a four-pillar participatory framework designed to realign autism research with community-defined goals. The framework calls for inclusive co-design practices, cultural contextualization, accessible dissemination of research outcomes, and stronger accountability mechanisms to ensure that knowledge reaches—and resonates with—those it is meant to benefit. This approach offers a new direction for autism research in the Arab region, moving from top-down methodologies to community-rooted partnerships. By centering lived experience, honoring cultural identity, and committing to shared accountability, the proposed framework has the potential to transform how research is conducted and applied—not just in Qatar, but across similar underrepresented settings.

Keywords- Autism spectrum disorder, Community engagement, Participatory research, Cultural adaptation, Co-design, Arabic context, Neurodiversity, Assistive technology, Research priorities, Stakeholder involvement.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) affects approximately 1 in 100 individuals globally, with increasing recognition of the importance of inclusive, community-centered approaches to research and innovation [1]. However, despite notable advances in neuroscience, genetics, artificial intelligence, and behavioral sciences, a persistent gap remains between academic research outcomes and the lived experiences of autistic individuals and their families [2].

This gap is particularly pronounced in underrepresented cultural and linguistic contexts, where Western-developed interventions and assessment tools may lack cultural validity and appropriateness [3], [4]. In the Arab region, recent research has highlighted significant disparities in autism research representation and the urgent need for culturally adapted approaches [5], [6].

The emergence of participatory research methodologies in autism studies has shown promise in addressing these disparities. Hijab et al. (2024) demonstrated in their systematic review that co-design approaches involving autistic children can provide substantial benefits over traditional design methodologies, particularly when adaptive techniques accommodate diverse communication abilities and cultural contexts [7]. Similarly, several studies have emphasized the importance of accessibility-first approaches in developing inclusive technologies for individuals with disabilities [8], [9].

The AutismTech 2025 conference, held in Doha, Qatar, provided a unique opportunity to explore these challenges within the Arab context. As a rapidly growing technological hub with increasing awareness of autism and disability rights, Qatar represents an important case study for understanding how emerging economies can develop culturally responsive autism research ecosystems [10].

Literature Review

Participatory Research in Autism

The shift toward participatory research in autism has gained momentum over the past decade, driven by advocacy from the autistic community and recognition of the limitations of traditional research approaches [11]. Pellicano et al. (2014) identified significant misalignment between researcher and community priorities, with academic research often focusing on causal mechanisms while communities prioritized practical interventions for daily living [2].

Recent work by Pickard et al. (2022) found that while researchers increasingly recognize the value of participatory approaches, implementation remains challenging due to institutional barriers and methodological uncertainties [12]. Den Houting et al. (2021) emphasized that meaningful participation requires more than consultation demands shared power in research design, implementation, and dissemination [13].

Co-design and Technology Development

Co-design methodologies have shown particular promise in autism technology development. Hijab et al. (2024) conducted a comprehensive systematic review of co-design processes involving autistic children, identifying 82 studies that demonstrated the benefits of inclusive design approaches [7]. Their analysis revealed four key themes: advances in co-design objectives, participant recruitment strategies, core methodological approaches, and challenge management techniques.

Building on this foundation, Hijab et al. (2025) demonstrated practical implementation of co-design principles in developing collaborative play technologies for autistic children in Qatar [14]. Their work involved nine autistic and four non-autistic children and revealed important insights into social interaction preferences and the potential for technology to facilitate inclusive play experiences.

Cultural Adaptation and Arab Context

The importance of cultural adaptation in autism research has been increasingly recognized, particularly in non-Western contexts. Al Maskari et al. (2018) conducted a systematic review of cultural adaptations of autism screening tools in non-English speaking countries, finding significant variations in adaptation approaches and validation outcomes [15].

In the Arab region specifically, recent research has begun to address historical gaps in autism research representation. Bahameish et al. (2025) examined autistic traits and internet use patterns in Qatar, providing rare empirical data on autism experiences in the Middle East [5]. Their work highlighted the need for culturally validated assessment tools and region-specific research priorities.

Al-Thani et al. (2021) explored stakeholder perspectives on assistive technology adoption among older adults in Qatar, revealing important insights about cultural barriers to technology acceptance that may extend to autism contexts [3]. Their stakeholder engagement methodology provides a model for inclusive research approaches in the region.

Research Gaps and Opportunities

Despite these advances, significant gaps remain in our understanding of how to effectively bridge research-community divides in autism, particularly in non-Western contexts. Current literature lacks comprehensive frameworks for implementing participatory research at scale, and few studies have examined the specific challenges and opportunities present in the Arab region.

The present study addresses these gaps by synthesizing expert perspectives from a diverse stakeholder panel and developing a practical framework for culturally responsive autism research that can inform both regional and global practice.

Methods

Study Design

This study employed a qualitative approach using expert panel methodology to synthesize stakeholder perspectives on autism research-community gaps. The research was conducted as part of the AutismTech 2025 conference held in Doha, Qatar, from April 15-17, 2025.

Panel Structure and Participants

Two complementary panel discussions were organized to explore different aspects of the research-community gap:

| Panel | Focus | Participants | Moderator |

| Panel 1 | Community Voices and Research Priorities | 3 panelists + 1 moderator | Sabika Shaban (QADR[1]/HBKU[2]) |

| Panel 2 | Research Expectations and Responsibilities | 3 panelists + 1 moderator | Dr. Achraf Othman (Mada[3] Qatar) |

Participant Perspectives

The study involved eight key stakeholders representing diverse perspectives within the autism community, including holding multiple roles:

| Stakeholder Category | Participants | Roles |

| Community Representatives | 4 | Self-advocate, parents |

| Education/Clinical Experts | 2 | Special educator, Consultant psychiatrist |

| Technology Specialists | 3 | Technology developers |

| Academicians | 4 | University professionals, researchers |

Data Collection

Panel discussions were conducted in English with simultaneous Arabic interpretation available. Each panel session lasted 40 minutes and followed a semi-structured format with predetermined themes while allowing for organic dialogue development. Detailed notes were taken by moderators.

Data Analysis

We employed thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase approach: (1) familiarization with data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report [16]. Two researchers independently coded the data, with disagreements resolved through discussion and consultation with a third researcher.

Results

Panel 1: Community Voices and Research Priorities

Panel 1 discussions revealed critical community concerns around the practical relevance of current research. The self-advocate participant (Mursi Seraj) emphasized the importance of research that directly addresses daily living challenges: “We need research that helps us navigate the real world, not just understand our brains.”

Parent participant Hayat Zakaria drew attention to the cultural and linguistic disconnect in existing autism interventions, particularly for adults over the age of 25. She emphasized that many of the available tools were designed with Western assumptions and fail to address the realities of lifelong care in Arab families. She shared her personal experiences on the disparities that exist between existing tools and services and her family’s cultural identity and language, and the challenges for adults with autism like her sons to be able to access technological support to improve their quality of living.

The learning support teacher (Ranjana Ranganathan) stressed the importance of practical, implementable solutions in educational settings: “Research findings often give us insight into doable possibilities of successful outcomes for the child. If we could develop such action into consistent practice, involving all stakeholders, both at home and in school, as well as document their practical implementation, then they could serve as a reliable system to advance inclusion.”

Panel 2: Research Expectations and Responsibilities

Panel 2 discussions focused on researcher perspectives and institutional responsibilities. Dr. David Brown acknowledged historical oversights in community engagement: “We’ve been studying autism for decades, but too often without meaningfully involving autistic individuals in setting research priorities.”

Dr. John-John Cabibihan emphasized the need for interdisciplinary collaboration: “Technology solutions need to be developed in partnership with communities, not imposed upon them. This requires fundamental changes in how we approach research design.”

Dr. Asma Amin underscored the challenges of translating clinical research into practical outcomes, emphasizing the pressing need to bridge the gap between scientific findings and the quality of services available to autistic individuals. “We have a responsibility to ensure that research findings translate into improved services and support systems,” she stated. “This requires ongoing dialogue between researchers and service providers.” She also warned of a growing concern: the impact of technology addiction among children and youth, which not only complicates early screening and diagnosis but also interferes with the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Without addressing this digital dependency, she argued, both assessment and care risk becoming increasingly misaligned with the real needs of the autistic community.

Emergent Themes

Thematic analysis revealed four major themes that cut across both panels:

Theme 1: Practical Relevance Gap

Participants consistently identified a disconnect between research priorities and daily living needs. Research often focuses on theoretical understanding while communities need practical interventions for education, healthcare, employment, and independent living.

Theme 2: Cultural and Linguistic Barriers

Arabic-speaking participants highlighted the inadequacy of Western-developed tools and interventions. Cultural norms, family structures, and linguistic differences create significant barriers to implementing existing research findings.

Theme 3: Authentic Community Engagement

Both panels emphasized the need for genuine partnership rather than tokenistic consultation. Community members should be involved as equal partners throughout all research phases, from planning to dissemination.

Theme 4: Accountability and Accessibility

Participants stressed the need for research outcomes to be communicated in accessible formats and for researchers to be accountable for real-world impact. This includes ongoing feedback mechanisms and adaptation based on community input.

Discussion

Alignment with Existing Literature

Our findings align closely with international literature on participatory autism research. The practical relevance gap identified by our participants mirrors findings from Pellicano et al. (2014) and Roche et al. (2021), who documented similar misalignments between research and community priorities in Western contexts [2], [11].

The emphasis on cultural adaptation resonates with recent work by Al-Thani and colleagues, who have consistently highlighted the importance of culturally responsive approaches in technology and disability research [3], [5]. Hijab et al. (2024)’s systematic work on co-design methodologies provides a methodological foundation for implementing the participatory approaches called for by our panel participants [7].

Regional Context and Implications

The Arab region faces unique challenges in autism research and service provision. Historical underrepresentation in international research, combined with rapid social and technological change, creates both obstacles and opportunities for developing innovative approaches [6].

Qatar’s emergence as a research hub, exemplified by institutions like Mada Qatar Assistive Technology Center and the growing research portfolio at institutions like HBKU, provides a model for how regional capacity can be developed while maintaining cultural authenticity [8].

Methodological Contributions

While expert panel methodology has been used in autism research [17], our approach of combining community and researcher perspectives in parallel panels provided unique insights into the different priorities and constraints faced by various stakeholders.

The focused stakeholder representation (eight participants) allowed for in-depth exploration of themes while maintaining manageable group dynamics. This approach may be particularly valuable in contexts where autism community organizing is still developing and where intimate dialogue may be more culturally appropriate than large-scale forums.

Proposed Framework for Culturally Responsive Autism Research

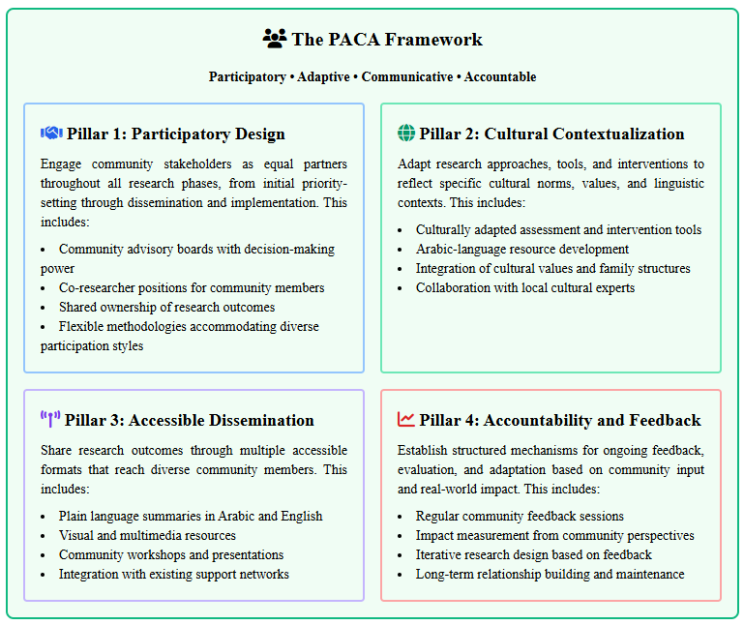

Based on the synthesis of panel discussions and alignment with existing literature, we propose a comprehensive four-pillar framework for bridging the gap between autism research and community needs:

Figure 1. The PACA Framework

Figure 1. The PACA Framework

Implementation Strategies

Successful implementation of the PACA framework requires systematic changes at multiple levels:

| Level | Strategy | Key Actions |

| Individual Researcher | Capacity Building | Training in participatory methods, cultural competency, accessible communication |

| Institutional | Policy Reform | Tenure criteria including community impact, funding for community engagement |

| Funding Agency | Priority Setting | Community engagement requirements, long-term relationship funding |

| Community | Capacity Development | Research literacy programs, leadership development, advocacy training |

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. The study involved a relatively small number of participants (n=8) from a single conference context, which may limit generalizability. However, the focused expert panel approach allowed for in-depth exploration of themes and is appropriate for framework development research.

The geographic focus on Qatar and the Arab region may limit applicability to other cultural contexts, though the underlying principles may be transferable. Additionally, the conference setting may have influenced participant responses, potentially emphasizing positive aspects of technology and innovation.

Future research should validate the proposed framework through implementation studies and expand the geographic and cultural scope of stakeholder consultation. Longitudinal studies examining the impact of framework implementation on research outcomes and community satisfaction would strengthen the evidence base.

Conclusions

This study presents a potential participatory framework for culturally responsive autism research that addresses critical gaps between academic research and community needs. The PACA framework (Participatory, Adaptive, Communicative, Accountable) provides a practical roadmap for researchers and institutions seeking to develop more inclusive and impactful research approaches.

The regional focus on the Arab context highlights the importance of cultural adaptation in autism research and demonstrates how local expertise can contribute to global knowledge. The collaborative involvement of established researchers like Dena Al-Thani and Achraf Othman, who have pioneered participatory approaches in regional autism and assistive technology research, provides a strong foundation for implementation.

Moving forward, successful implementation of this framework will require sustained commitment from multiple stakeholders, including researchers, institutions, funding agencies, and community organizations. The potential benefits—more relevant research, improved services, and enhanced quality of life for autistic individuals and families—justify the investment required for this transformation.

As the autism research field continues to evolve, frameworks like PACA can help ensure that this evolution is guided by community voices and cultural wisdom, ultimately creating a more inclusive and effective research ecosystem that serves all members of the autism community.

Acknowledgments

We thank all panel participants for their generous contribution of time and expertise. Special acknowledgment goes to the self-advocate and parent participants who shared their personal experiences and insights. We also thank the AutismTech 2025 organizing committee for providing the platform for these important discussions.

References

[1] M. J. Maenner, ‘Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2018’, MMWR Surveill. Summ., vol. 70, 2021.

[2] E. Pellicano, A. Dinsmore, and T. Charman, ‘Views on researcher-community engagement in autism research in the United Kingdom: A mixed-methods study’, PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 10, p. e109946, 2014.

[3] D. Al Thani, A. Hassan, H. Chalghoumi, A. Othman, and S. Hammad, ‘Addressing the Digital Gap for the Older Persons and their caregivers in the State of Qatar: A Stakeholders’ Perspective’, in 2021 8th International Conference on ICT & Accessibility (ICTA), IEEE, 2021, pp. 01–06.

[4] S. Soto, K. Linas, D. Jacobstein, M. Biel, T. Migdal, and B. J. Anthony, ‘A review of cultural adaptations of screening tools for autism spectrum disorders’, Autism, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 646–661, 2015.

[5] M. Bahameish, D. Al-Thani, M. Qaraqe, and C. Montag, ‘Autistic Traits and Internet Use Disorder Tendencies in the Middle East: Insights from Qatar’, J. Technol. Behav. Sci., pp. 1–16, 2025.

[6] H. Hussein, G. R. Taha, and A. Almanasef, ‘Characteristics of autism spectrum disorders in a sample of egyptian and saudi patients: transcultural cross sectional study’, Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 34, 2011.

[7] M. H. F. Hijab, B. Banire, J. Neves, M. Qaraqe, A. Othman, and D. Al-Thani, ‘Co-design of technology involving autistic children: A systematic literature review’, Int. J. Human–Computer Interact., vol. 40, no. 22, pp. 7498–7516, 2024.

[8] A. Othman et al., ‘Accessible Metaverse: A theoretical framework for accessibility and inclusion in the Metaverse’, Multimodal Technol. Interact., vol. 8, no. 3, p. 21, 2024.

[9] C. Y. Zhang and K. Chemnad, ‘Is the metaverse accessible? An expert opinion’, Nafath, vol. 9, no. 25, 2024, Accessed: Aug. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://nafath.mada.org.qa/nafath-article/mcn2507/

[10] A. Lahiri, A. Othman, D. A. Al-Thani, and A. Al-Tamimi, ‘Mada Accessibility and Assistive Technology Glossary: A Digital Resource of Specialized Terms’, in ICCHP, 2020, p. 207.

[11] L. Roche, D. Adams, and M. Clark, ‘Research priorities of the autism community: A systematic review of key stakeholder perspectives’, Autism, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 336–348, 2021.

[12] H. Pickard, E. Pellicano, J. Den Houting, and L. Crane, ‘Participatory autism research: Early career and established researchers’ views and experiences’, Autism, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 75–87, 2022.

[13] J. Den Houting, J. Higgins, K. Isaacs, J. Mahony, and E. Pellicano, ‘“I’m not just a guinea pig”: Academic and community perceptions of participatory autism research’, Autism, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 148–163, 2021.

[14] M. H. F. Hijab et al., ‘Let’s join the toy inventors: designing an inclusive collaborative play toy with and for autistic children’, CoDesign, pp. 1–36, 2025.

[15] T. S. Al Maskari, C. A. Melville, and D. S. Willis, ‘Systematic review: cultural adaptation and feasibility of screening for autism in non-English speaking countries’, Int. J. Ment. Health Syst., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 22, 2018.

[16] V. Braun and V. Clarke, ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qual. Res. Psychol., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 77–101, 2006.

[17] T. W. Benevides et al., ‘Listening to the autistic voice: Mental health priorities to guide research and practice in autism from a stakeholder-driven project’, Autism, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 822–833, 2020.

[1] Qatar Disability Resource (QADR)

[2] Hamad Bin Khalifa University (HBKU)

[3] MADA: Qatar Assistive Technology Center